Not many museums have mounted a collection of photographs and ephemera that chronicle the history of worker organizing and the labor movement. That’s not surprising. Museums and their special exhibits are underwritten by foundations, corporations and the very rich—funders that, by and large, are not known for their concern for those who toil for a living and seek to better their lives through union representation.

Not many museums have mounted a collection of photographs and ephemera that chronicle the history of worker organizing and the labor movement. That’s not surprising. Museums and their special exhibits are underwritten by foundations, corporations and the very rich—funders that, by and large, are not known for their concern for those who toil for a living and seek to better their lives through union representation.

The annual Met Gala, the high-society benefit for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, has revolved around couturiers like Coco Chanel and Alexander McQueen or sartorial themes from camp to Catholicism. Television viewers have yet, however, to see celebrities like Lady Gaga done up in a McDonald’s uniform or other industrial-designed attire walk the red carpet across David H. Koch Plaza—the $65 million gift to the Met from David H. Koch.

All of which makes City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York a rare and radical gem of a show.

One enters this special exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York through a montage of photographs of demonstrators holding placards that read: “Abolish Slavery,” “We Want Respect for Workers,” “Put Black Men to Work or Stop Construction,” “Mt. Sinai Workers Can’t Live on $32 a Week—On Strike” and “Carwasheros al Poder” (Power to the Carwashers).

The exhibit begins with the enslaved people of New York (40% of New York households owned one or more workers in colonial days) and continues through today’s movement of minimum-wage slaves and the Fight for $15.

If the overarching theme of City of Workersis collective action—how New Yorkers formed unions and gained better working conditions and better pay—the subtext is that cooperation among black, brown and white workers made those advances possible. In the age of Trump, that message bears repeating.

In the book that accompanies the exhibit, labor historian Joshua B. Freeman writes, “The city of New York would not exist in anything like its current form without the struggles of working people over the past three centuries.” Similar stories could be told of any number of cities across the country—cities where labor history exhibits could be mounted, if not for want of museum space, cities where the struggle of workers continues to this day.

City of Workers, sponsored by the union-friendly Puffin Foundation of Teaneck, N.J., is on exhibit through Jan. 5, 2020, at the Museum of the City of New York, just one mile north of the Met and across from Central Park. While you are there, check out Activist New York, a permanent exhibit on the city’s history of political agitation in the Puffin Foundation Gallery.

All images courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

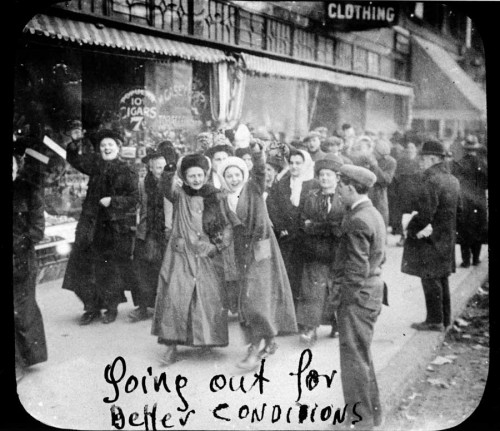

(A few of the New York shirtwaist workers, most of whom were Jewish women, went on strike in 1909 for better pay, working conditions and shorter hours. The strike, known as the Uprising of the 20,000, targeted more than 600 garment shops and factories.)

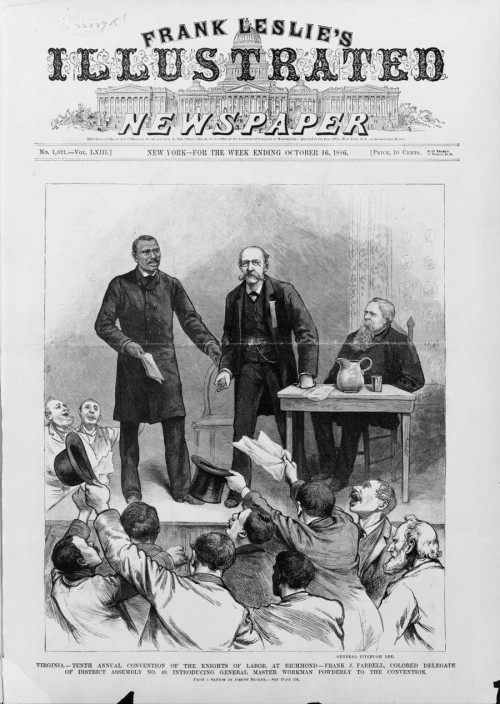

(Frank J. Ferrell, a black delegate of the New York City chapter of the Knights of Labor addresses the group at their 1886 convention in Richmond, Va. When Ferrell was denied a room at a local hotel where he and his New York colleagues had a reservation, they decamped en masse for less racist accommodations.)

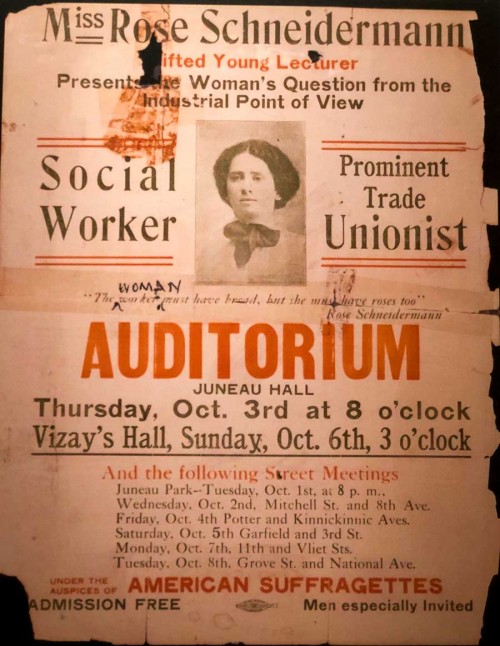

(This poster advertises a 1912 Milwaukee talk by Rose Schneidermann, a socialist feminist who had worked in the garment industry. Rose is best known for her speechthat same year to middle-class suffragettes in Cleveland: “What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist … The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too. Help, you women of privilege, give her the ballot to fight with.”)

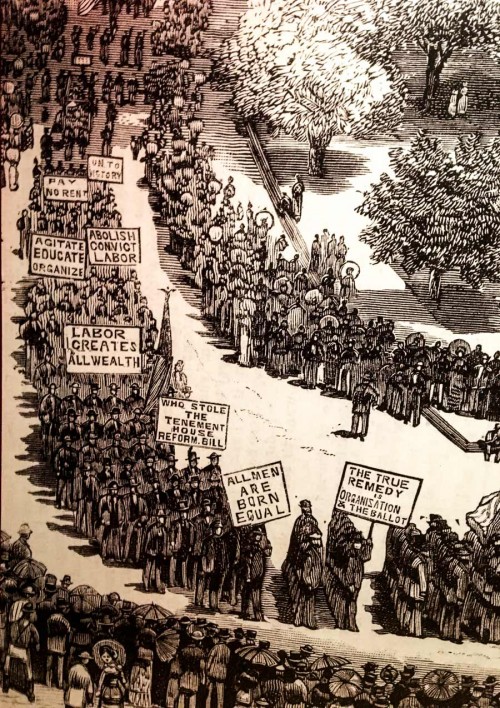

(In 1882, members of the Knights of Labor and the Central Labor Union gathered in New York’s Union Square for the first-ever Labor Day parade.)

(In 1965, in front of Macy’s, members of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union picket Judy Bond, a “runaway plant” that had moved to the South. The union’s multi-year campaign included shopping bags that read, “Judy Bond Inc., On Strike, Don’t Buy Judy Bond Blouses.” According to the union, strikers handed out more than 3 million bags in 1963.)

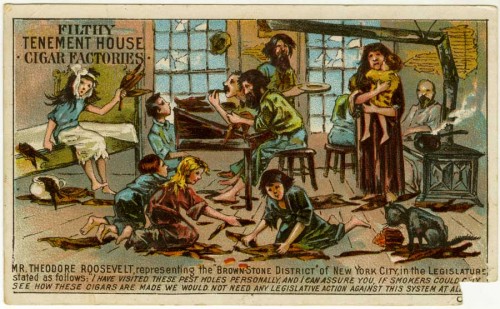

(“Filthy Tenement House Cigar Factories” postcard, circa 1885.)

Amalgamated Dwellings is the oldest limited-equity housing cooperative in the U.S. Founded in 1927 in the Bronx by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, the co-op was established to provide affordable housing for workers. Today, Amalgamated is home to more than 1,400 families.

(In 1936, in the Poconos, members of New York’s Communist-led Dressmakers’ Union (Local 22) relax at Unity House. Local 22 and Local 25 purchased the 750-acre retreat, which had formerly been a tony resort for German Jews, in 1919.)

This blog was originally published at In These Times on August 28, 2019. Reprinted with permission.

His reporting on environmental health issues, national security scandals and the Iran Contra affair has landed in newspapers and magazines around the country, including the New York Times, the Utne Reader, the Capital Eye and many others.

He is the co-author of the book “Was The 2004 Presidential Election Stolen?,” with Steven F. Freeman.

Before joining In These Times, Bleifuss was director of the Peace Studies Program for the University of Missouri, a features writer for the Fulton Sun in Fulton, Missouri, and a freelance journalist in Spain.

Bleifuss currently serves on the advisory board of The Public Square, a program of the Illinois Humanities Council.